Exploring the communication of ecological messages through art

Scroll down for Spanish

In science we are taught to write to inform, persuade and describe. We’re taught to pick out our key take-home messages, to make it clear what we want the reader to go away with and why the evidence supports us. “My research is important!” we try to scream through technical sentences, twisted into tightly cut abstracts, whittled down through iterations of edits to meet word counts and antiquated academic writing practices. The purpose of a scientific paper is to make a point, and convince the reader to agree with you, largely without using emotive prose, only the cold tongue of scientific language.

Over the last year, in which I’ve been conducting an MSc dissertation in the SalGo team, I’ve been reflecting on how we communicate messages about ecology. Part of this reflection was prompted by participating in the Flute and Bowl, an Oxford-based art and ecology society. The Flute and Bowl operates to provide a platform to bring together diverse disciplines and encourage more dynamic ways of tackling the environmental crisis in all its facets. As their website states, it is hoped that such collaboration will aid “transitioning our cultural relationship to the natural world from one of exploitation, disconnect and antagonism to one of reciprocity, interconnection and mutualism.”[1]

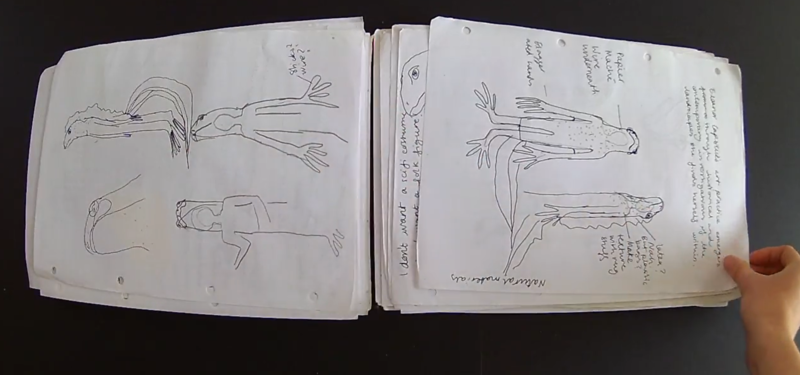

Photo 1: Eleanor’s sketchbook with drawings of newts, a newt costume, and notes (Credit: Eleanor Capstick). El libro de bocetos de Eleanor, con dibujos de tritones, un traje de tritón, y notas (Crédito: Eleanor Capstick).

Through the Flute and Bowl, I’ve been working with an artist on a project linked to my MSc dissertation research, into the habitat requirements of great crested newts. This process has made me reflect on the differences and similarities in which we deliver messages through art and science. The artist with whom I worked is Eleanor Capstick[2], a fine art student at Oxford’s Ruskin School of Art, whose previous work focussed on the landscape and history of Otmoor, a nearby RSPB wetland. From discussing art, ecology and our piece, I’ve learned more about the way artist students are encouraged approach incorporating any messages into their work. Eleanor says that the art school tutors encourage them to “avoid the desire to control viewer responses”, essentially to create a piece of work and leave it for the viewer to judge its meaning and make up their own take-home messages.

In our art piece, we are contemplating where we should fall on the continuum from leaving the piece completely open to interpretation, or trying to convince the audience to take away a certain message. If it is a piece of political art, to what extent should we try to channel the viewer into responding in a certain way? And what is the best way to have an impact, make change, inform or persuade? I think these are interesting questions to consider for those working in ecology too – are we communicating our work in a way that leads to the real-world effects we are hoping for? As someone with a passion for newt conservation, I want to make sure the viewer comes away from our art piece feeling similarly positive towards newts, but that’s inevitably impossible to guarantee with a piece of art that is open to interpretation. I’ve found it really interesting to question the different methods of communicating an ecological or conservation message.

I was delighted that Eleanor become captivated by newts too over the process of our collaboration. She admitted that she had no prior interest in amphibians, but luckily my own fascination (read: obsession) with newts was enough to get her interested. Her own research for the project introduced me to new newt-related resources and readings that I wouldn’t have otherwise come across, such as a map of local names for newts from across Britain, which included ‘aster’, ‘asgel’, ‘wet-effet’, and my personal favourite ‘water-swift’ from Suffolk[3].

Photo 2: Image of a pond at night, illuminated by a torch, taking during a newt survey (Credit: Emily Seccombe). Imagen de un estanque por la noche, iluminado por una linterna, durante un muestreo de tritones (Crédito: Emily Seccombe).

There are many fascinating things about the ecology and biology of great crested newts, but we chose to focus on the politicisation of the newt. In particular, we wanted to examine the way newts have been used by politicians as a stand-in for nature-protection bureaucracy. Newts made the headlines earlier this year when UK Prime Minister Boris Johnson said that “Newt-counting delays are a massive drag on the prosperity of this country”[4]. Lord Borwick-Mayfield, a housing developer and hereditary peer, who made a similar comment in a 2016 House of Lords speech. Lord-Borwick-Mayfield suggested that great crested newts, which he described as “an awful amphibian”, may be planted onto development sites to disrupt progress[5]. This act of sabotage is an undocumented possibility, lacking any firm evidence. We wanted to explore this idea, and have been working on a piece of parafictional art[6] combining costume, performance, film, photography and written materials. The resulting work will be part of the Flute and Bowl exhibition in 2021, details to be confirmed, pending COVID-restrictions.

As well as being thoroughly thought-provoking and enjoyable, I’ve found this experience to be important for the way I communicate ecological messages. It has certainly made me reflect more on the separation between science and art, and how the two can (and indeed need to) come together for conservation projects.

Emily Seccombe

[3] https://twitter.com/tweetolectology/status/1169497891871895552?s=20&fbclid=IwAR3ORtJVAZFyyqX5_5_NHq-ljFKg32RY453RuGEQgeRSCVYFFYBIkchvx3A

[6] For some very interesting reading about parafiction in art, see Make Believe: Parafiction and Plausibility (2009) by Carrie Lambert-Beatty https://scholar.harvard.edu/lambert-beatty/publications/make-believe-parafiction-and-plausibility

[SPA]

En la ciencia, se nos enseña a escribir para informar, persuadir y describir. Se nos enseña a elegir nuestros mensajes clave, para aclarar lo que queremos que se quede en la mente del lector y qué evidencia nos respalda. "¡Mi investigación es importante!" tratamos de gritar a través de clamados técnicos, a la par retorcidos en breves resúmenes, reducidos a través de iteraciones de ediciones para cumplir con el conteo de palabras y prácticas anticuadas de escritura académica. El propósito de un artículo científico es dejar claro un punto y convencer al lector de que esté de acuerdo contigo, en gran parte sin usar una prosa emotiva, sino sólo la fría lengua del lenguaje científico.

Durante el último año, en el que estuve realizando una tesis de maestría en el SalGo Team, estuve reflexionando sobre cómo comunicamos mensajes sobre la ecología. Parte de esta reflexión fue motivada por su participación en Flute and Bowl, una sociedad de arte y ecología con sede en Oxford. Flute and Bowl proporciona una plataforma para reunir diversas disciplinas y fomentar formas más dinámicas de abordar la crisis ambiental en todas sus facetas. Como dice su sitio web, se espera que dicha colaboración ayude a “hacer la transición de nuestra relación cultural con el mundo natural de una relación de explotación, desconexión y antagonismo a una de reciprocidad, interconexión y mutualismo”.

A través de Flute and Bowl, he estado trabajando con una artista en un proyecto relacionado con la investigación de mi tesis de maestría, sobre los requisitos de hábitat de los tritones encrestados. Este proceso me ha hecho reflexionar sobre las diferencias y similitudes en las que transmitimos mensajes a través del arte y la ciencia. La artista con la que trabajé es Eleanor Capstick, una estudiante de bellas artes en la Escuela de Arte Ruskin de Oxford, cuyo trabajo anterior se centró en el paisaje y la historia de Otmoor, un humedal cercano de la RSPB. Al hablar sobre arte, ecología y nuestra obra, he aprendido más sobre la forma en que se anima a los estudiantes de artistas a abordar la incorporación de mensajes en su trabajo. Eleanor dice que los tutores de la escuela de arte los animan a “evitar el deseo de controlar las respuestas del espectador”, esencialmente para crear una obra y dejar que el espectador juzgue su significado y cree sus propios mensajes para llevar a casa.

En nuestra obra de arte, estamos contemplando dónde deberíamos caer en el continuo desde dejar la pieza completamente abierta a la interpretación o tratar de convencer a la audiencia de que se lleve un determinado mensaje. Si se trata de una obra de arte político, ¿hasta qué punto deberíamos intentar canalizar al espectador para que responda de cierta manera? ¿Y cuál es la mejor manera de impactar, hacer cambios, informar, o persuadir? Creo que estas son preguntas interesantes a considerar también para quienes trabajan en ecología: ¿estamos comunicando nuestro trabajo de una manera que conduzca a los efectos en el mundo real que esperamos? Como alguien apasionado por la conservación de los tritones, quiero asegurarme de que el espectador salga de nuestra obra de arte sintiéndose igualmente positivo hacia los tritones, pero eso es inevitablemente imposible de garantizar con una obra de arte abierta a la interpretación. Me ha resultado muy interesante cuestionar los diferentes métodos de comunicar un mensaje ecológico o de conservación.

Me encantó que Eleanor se sintiera cautivada por los tritones también durante el proceso de nuestra colaboración. Ella admitió que no tenía ningún interés previo en los anfibios, pero afortunadamente mi propia fascinación (léase: obsesión) con los tritones fue suficiente para interesarla. Su propia investigación para el proyecto me presentó nuevos recursos y lecturas relacionados con el tritón que de otro modo no habría encontrado, como un mapa de nombres locales para tritones de toda Gran Bretaña, que incluía 'aster', 'asgel', ' wet-effet ', y mi favorito personal 'water-swift' de Suffolk.

Hay muchas cosas fascinantes sobre la ecología y la biología de los tritones encrestados, pero decidimos centrarnos en la politización del tritón. En particular, queríamos examinar la forma en que los políticos han utilizado los tritones como sustituto de la burocracia de protección de la naturaleza. Los tritones aparecieron en los titulares a principios de este año cuando el primer ministro del Reino Unido, Boris Johnson, dijo que "los retrasos en el conteo de tritones son un lastre enorme para la prosperidad de este país". Lord Borwick-Mayfield, un planificador de viviendas, hizo un comentario similar en un discurso de la Cámara de los Lores en 2016. Lord-Borwick-Mayfield sugirió que se pueden plantar grandes tritones encrestados, al cual él describió como "un terrible anfibio", en los sitios de desarrollo para interrumpir el progreso. Este acto de sabotaje es una posibilidad indocumentada, sin evidencia firme. Quisimos pues explorar esta idea y hemos estado trabajando en una obra de arte paraficción que combina vestuario, performance, cine, fotografía y materiales escritos. El trabajo resultante será parte de la exposición Flute and Bowl en 2021, detalles por confirmar, pendientes de restricciones COVID.

Además de ser muy estimulante y agradable, he encontrado que esta experiencia es importante para la forma en que comunico mensajes ecológicos. Ciertamente me ha hecho reflexionar más sobre la separación entre ciencia y arte, y cómo los dos pueden (y de hecho necesitan) unirse para proyectos de conservación.

Escrito por Emily Seccombe. Traducido por Sam Gascoigne & Rob Salguero-Gómez via Google Translate.